from an earlier post:

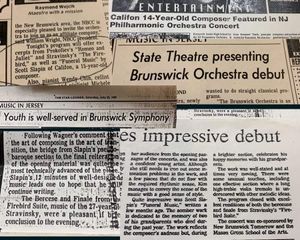

As a young teenager, I wrote orchestral music that was performed in my home state of New Jersey by the Philharmonic of New Jersey, the Hunterdon Symphony, the New Jersey Youth Symphony, and the Brunswick Symphony Orchestra in the New Jersey State Theater. A little later I played Berlioz' Harold In Italy with the Central Jersey Symphony, Bloch's Prayer and Paganini's Moses Variations (on the C String) with the Hunterdon Symphony, and Bach's Sixth Brandenburg with Peter Neubert and the Baroque Aria Ensemble (at Manhattan School of Music) under the direction of harpsichordist Kenneth Cooper.

I met Tanya playing in the Philadelphia Virtuosi Chamber Orchestra in 1999. (We were the whole viola section!) We also performed that two-viola Brandenburg concerto several times with various groups over the next few years before we turned our attention mainly to recital and orchestral music.

Tanya had previously been a member of the New World Symphony in Florida, the Chicago Civic Orchestra, and the Spoleto Festival Orchestras in Charleston, SC and in Spoleto, Italy. So I entered the orchestral world, and together we spent the next decade playing in nearly all fifty states and twenty countries. When Hurricane Katrina hit, we were playing in the New Orleans-based Louisiana Philharmonic, and we lost all of our stuff. (See 'New Orleans' blog post.) We participated in Hurricane Katrina relief concerts in New York City with the New York Philharmonic and from coast to coast with smaller ensembles.

When the economy collapsed in 2008, I was playing with the Cincinnati Symphony and Pops, held firmly to one season by an orchestra-wide hiring freeze. We also played down the road for a bit in the Louisville Orchestra. My first full-time position was as principal violist with the Knoxville Symphony and Chamber Orchestras, during which time Tanya was principal violist of the other full-time orchestra in eastern Tennessee, the Chattanooga Symphony and Opera. Not only did we tour the US extensively (and Europe quite a bit as well), we toured South America with Brazil's flagship orchestra, the São Paulo State Symphony. We spent a few months playing in their main hall as well, the world-renowned Sala São Paulo.

The orchestras in São Paulo and Cincinnati are internationally known and able to concentrate primarily on serious repertoire in their (quite impressive) main halls. They regularly bring in top guest conductors and soloists. Cincinnati had around 100 musicians when I was there, and São Paulo had at least 110 (and more on tour.) The 71-musician Louisville Orchestra (today reduced to 55 I believe) and the 60-some-musician New Orleans based Louisiana Philharmonic (the successor of the bankrupt New Orleans Symphony) probably had their best days, financially speaking, behind them. Some of my fondest memories though are from my first season in New Orleans (the only place we stayed long enough to become tenured), with Klauspeter Seibel (1936-2011) conducting in the Orpheum Theater. We played mostly serious music that season in good halls making little money. As the seasons passed, the calendar began to be filled more with concerts in churches and schools, parks gigs etc.

There are some people who try to spin the decline of a symphony orchestra as a positive development. They talk of exciting new ‘cooperative’ models, ‘bringing the music to the people’, ‘redefining the role of the symphony orchestra’ etc., but sadly this is just putting lipstick on the pig. The orchestras that have the funds to do so stick primarily to what they do best: playing serious orchestral music in an acoustically appropriate concert hall. It’s only out of desperation that you’ll find a full-time orchestra playing in a casino, at a horse-show, or on a parking lot.

The cattle-call audition circuit isn't easy. There is an increasing number of people who can play the excerpts well, and it’s a tremendous effort and expense to prepare a whole list of excerpts and concertos, fly to the city, stay in a hotel for a few days along with a hundred or more other contestants, all to compete for the same spot. The competition is more sport than musical performance: Who has the most consistency and endurance? (And in some cases, who has some help from on the inside?) We never 'played for anyone' (in the orchestra) before the audition, both for some ethical objections and out of pure laziness. (But mostly out of laziness.)

In general, the list of musical priorities is different for orchestral playing (especially the auditions), with metronomic rhythm, intonation and consistency on top. Other details that are important in solo playing barely register and often can get in the way. It's not easy for the jury either, locked in a room all day. What do you do when many candidates are playing the excerpts fairly well? It often comes down to finding some small, fairly irrelevant detail to weed people out. Whether auditioning in this way really finds the best person for the job is widely debated, with a few fragile egos on both sides of the argument.

And then there are the conductors! When Raphael Fruehbeck de Burgos (1933-2014) came to the Cincinnati Symphony to conduct Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique, he wasted no time. He showed what he wanted with the baton, allowing the musicians to play, and when he said something, it was short and to the point. Mostly he didn’t say much. This approach can make playing in an orchestra a joy. Unfortunately, there are at least as many semi-conductors out there as conductors.

Semi-conductors talk at length during rehearsals, often about things that are irrelevant to making the performance better. This takes away from the time the musicians have to play and usually bores them. (In this state, when a semi-conductor does say something important, many don’t notice.) Some semi-conductors are consumed with creating an ‘exciting’ performance at the expense of nuance, ensemble and intonation. Others may be obsessed with historical performance practices and endeavor to make your symphony orchestra sound like a period Baroque ensemble. Good conductors won’t micromanage in this way or attempt to radically change an ensemble’s sound.

We have some fond memories but we also had our fill. At its best, playing in an orchestra can be rewarding musically and you get to see a lot of places and play with a lot of great soloists. Some of the great string players with whom we got to share the stage include Itzhak Perlman, Leonidas Kavakos, Joshua Bell, Roberto Diaz, Yo-yo Ma, and Lynn Harrell. At its worst though, playing in an orchestra (at least full-time) can be physically taxing, uncreative, and often financially unstable. There will always be exceptions, but the trends don't look good. If it's not been your main dream since you were ten to play in a full-time symphony orchestra, you might find it to be more work than it's worth.

The music is absolutely great though! So we arranged a lot of it for viola duo. This also solves the long-standing problem of being at an orchestra concert and not being able to hear the viola section because of all the band instruments.

-Scott